I have decided to take the BBKA’s Module 2 exam, ‘Honeybee products and forage‘ in November. If I manage to pass, I’ll have passed Modules 1,2,3 & 6, which means I’ll be awarded the BBKA Intermediate Theory Certificate. Woo hoo!

But to pass I need to revise, something which often isn’t that appealing after a day at work. To kick me off, I’m going to learn a nice simple part of the syllabus: 2.24, a list of floral sources of unpalatable honey.

Unpalatable honey sources

The nectar of a few flowers produces honey which is unpleasant to taste, while a even smaller number of nectars are poisonous to bees or to humans when condensed into honey.

Commonest unpalatable honeys in the UK

- Privet – bitter taste

Celia Davis says of privet “it is very unlikely to be a problem as only very rarely are bees likely to collect large quantities of its nectar. Even so, a fairly small amount can damage the flavour of other nectars mixed with it.”

The Collins Beekeeper’s Bible comments that privet honey is “very strong flavoured, making it objectionable and unpalatable unless it is blended with lighter honeys.” It flowers during May to June.

Privet – © RHS 2002

- Common Ragwort – bitter taste

A bright, long-flowering plant which is very popular with bees. It’s tough and can grow in waste land, road sides, rough areas of parks etc.

Celia Davis describes ragwort as being “very attractive to bees… likely to produce quantities of extractable honey which smells horrible when it is fresh. If it is allowed to stand and granulate, the flavour improves and some beekeepers use it to blend with other, less flavoursome honeys. The plant contains several pyrrolizidine alkaloids which are responsible for the deaths of quite a few horses each year.” Ragwort honey is not thought to be dangerous to humans, as it seems likely that someone would have to eat a huge amount of honey to do themselves any harm.

Ted Hooper concurs, saying of ragwort honey “it is bright yellow and has so offensive an odour that when first extracted it is completely unpalatable. Once granulated however, the smell is lost and the honey quite good.”

Clive de Bruyn is also positive about ragwort honey, commenting in his classic book Practical beekeeping (1997) “The honey is a deep yellow with a strong flavour thought by some to be obnoxious. I personally find that it adds a bit of interest.” He goes on to say “Concern has been raised over the possibility of the honey containing pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs). A recent MAFF survey to assess levels of PAs in UK honey produced by bees with access to ragwort stated that there was no cause for alarm.” MAFF being the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, now known as DEFRA.

Unpleasant to some:

- Ivy – bitter taste

From the point of view of bees ivy must be a wonderful plant, flowering in September to October when little other forage is about.

However, some people find ivy honey far too bitter. Here’s a description of ivy honey from Cornwall by Elizabeth Gowing in her wee masterpiece, “The Little Book of Honey“:

The aroma is surprisingly flowery and light, but the taste is certainly not. It’s not a very sweet honey, and there is a bitter kick in it which hits you as the crystallised paste melts in your mouth.

I tried to place the flavour and then I got it – if a pointy-chinned woman got out her wand and turned a Stilton into a honey, this is what it would taste like.

And is that a good thing? I’m not convinced.”

To read more about Elizabeth’s bitter experiences with ivy honey, see her post Ivy honey from the Lizard Peninsula.

Yet others, myself included, prefer a honey that isn’t super-sweet and has more character. There are beekeepers with customers who specially request ivy honey. As I’ve got older my tastebuds have changed a bit and I’ve come to appreciate more sour and bitter foods such as olives, grapefruit juice and even gherkins, which used to make me wince.

Honeys which are poisonous to humans:

Many of the plants in the Ericaceae family, such as Rhododendron, Pieris, Agarista and Kalmia, produce poisonous nectars which contain grayanotoxins.

- Rhododendron spp

Cases of poisoning from this “mad honey” have been reported in Turkey and America. It’s said that ancient Greeks and Romans used to leave rhododendron honey in the path of invading armies. The soldiers would eat the sweet treat and end up vomiting and dizzy from grayanotoxin, a toxin contained in the honey. The effects rarely prove fatal but probably would have halted or slowed down the army for a couple of days.

The Collins Beekeeper’s Bible contains a tale of mad honey poisoning from the British botanist, plant-hunter and explorer Frank Kingdon-Ward. His memoir Plant-hunter’s Paradise (1937) vividly describes his experiences with rhododendron honey in northern Burma, near Tibet. The effect on the honey on him and his companions was a delirium similar to acute alcohol poisoning. Strangely the local Tibetans seemed to eat it without ill effects – or perhaps they just ate less than the greedy Europeans?

Ted Hooper mentions a case of bee deaths in the Isle of Colonsay in 1955 – the island was planted with a large number of Rhododendron thomsonii which subsequently poisoned whole colonies.

Rhododrendrons are widely grown in the UK but I haven’t heard of any reported cases of people here being affected by the honey; Celia Davis suggests this is because honey bees are not very interested in their flowers. This is reportedly the case in Ireland, where Rhododendron ponticum was introduced in the late 18th century and has now spread over large swathes of the countryside. Yet in Ireland its flowers are visited mainly by bumblebees, with occasional visits from solitary bees, flies, ants and wasps – but hardly ever honey bees.

Dr Jane Stout, a researcher at Trinity College, Dublin, has found that the grayanotoxins in rhododendron nectar have no obvious effect on worker bumblebees, yet will cause honey bees to die within hours. In both honey bees and humans, grayanotoxins keep the sodium channels present in nerve and muscle cells held open, so that neutrons keep firing until they are fatigued. The effect on Irish honey bees is palpitations, paralysis and death. Stout believes honey bees living within the rhododendron’s native range across Turkey to Georgia and southern Spain and Portugal have probably evolved to resist the toxins (‘Bitter sweet nectar: why some flowers poison bees‘ by Stephanie Pain (BBKA News, February 2016).

See more:

- Grayanotoxin Poisoning: ‘Mad Honey Disease’ and Beyond

A scientific paper on mad honey. Contains a fascinating description from the Greek warrior-writer Xenophon in 401 BC on the effects of the honey on an army – “those who had eaten a great deal seemed like crazy, or even, in some cases, dying men”. - A rare case of “honey intoxication” in Seattle

Rusty at Honey Bee Suite reports on the case of a man poisoned by honey purchased at a local farmer’s market. Like Celia Davis, Rusty’s observations have led her to believe “that rhododendron is not a preferred forage for honey bees and they probably collect it only in rare circumstances when other more favorable blooms are not available.” – EDIT: please see brookfieldfarmhoney‘s comment below on 16th Jan 2015 for the inside scoop on this – the scientist involved had his words twisted by the media. - “Mad Honey” sex is a bad idea

That got your attention! - Hallucinogen Honey Hunters documentary

Added after P&B mentioned it in the comments below – thanks! A tribe in Nepal hunt wild rhododendron honey with natural psychoactive properties. One falls unconscious after overdosing on the honey.

Photo of rhododendron by Dendroica cerulean

Kalmia latifolia

Commonly called mountain-laurel. This grows in the UK, but not in large enough quantities to cause problems. It is native to the eastern U.S.

According to Wikipedia’s entry on Kalmia latifola:

“The green parts of the plant, flowers, twigs, and pollen are all toxic, including food products made from them, such as toxic honey that may produce neurotoxic and gastrointestinal symptoms in humans eating more than a modest amount. Fortunately the honey is sufficiently bitter to discourage most people from eating it, whereas it does not harm bees sufficiently to prevent its use as winter bee fodder. Symptoms of toxicity begin to appear about 6 hours following ingestion. Symptoms include irregular or difficulty breathing, anorexia, repeated swallowing, profuse salivation, watering of the eyes and nose, cardiac distress, incoordination, depression, vomiting, frequent defecation, weakness, convulsions, paralysis, coma and eventually death.”

So please don’t go trying it.

Nectars which are poisonous to bees?

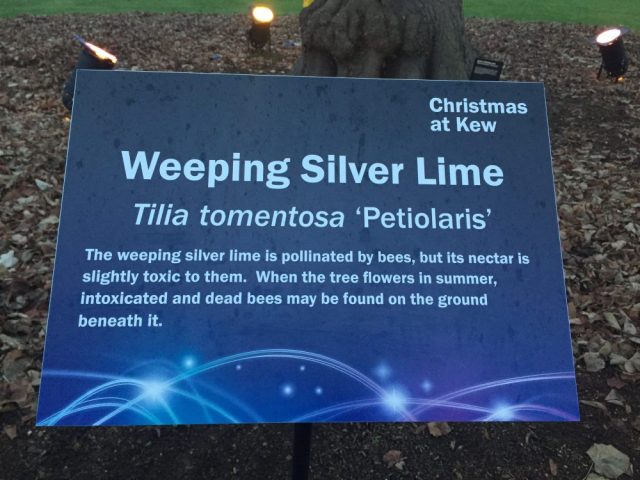

- Silver lime

- Silver pendant lime, also known as weeping lime

Some loopy plants make themselves poisonous to their own pollinators – or do they?

There has been some disagreement about whether lime trees poison bumble-bees, or bumble-bees run out of energy whilst feeding on them and die.

In 1997 Clive de Bruyn observed that “The culprits are mainly the late flowering species during dry weather when the nectar is concentrated… Such poisoning is not common and is dependent on the season, district and species of lime. One species that is known to affect bees is the pendant silver lime Tulia petoliaris, a beautiful tree, symmetrical with a rounded top. It can grow to 24m (80ft). Bees appear to get drunk on the nectar, and bumble bees are especially prone. They can sometimes be found dead under the trees in great numbers.”

However, more recent research seems to indicate that the cause of bumbles being found dead under lime trees is their foraging behaviour, rather than toxic nectar. Science writer Philip Strange has left some very useful comments below; as he sums up: “It seems they continue feeding on lime nectar even when levels are low and so they run out of energy. Honeybees don’t do this, they look elsewhere before they exhaust themselves.”

Angela Woods of the London Beekeepers Association also left me a plausible comment on a Facebook discussion I started – “Perhaps it is because bumbles have less stores in their nests and this tree tends to flower in the ‘gap’ when other sources of nectar are scarce … I was called out last summer to a street in Holland Park lined with silver limes and there were tons of poor bumbles dead under each tree. It was depressing to see.”

This effect has been noticed at Kew Gardens – see the photo below of a sign by a Weeping Silver Lime tree there. Research between Kew and the Wellcome Chemical Research laboratories in the 1930s suggested that it was the high concentration of oxalic acid in the nectar, or the rare sugar melexitose present in the honey-dew, that was intoxicating bees on Tilia petolaris. There’s an interesting update to this in a September 2017 Kew Science blog post, Do lime trees kill bees? The authors, Hauke Hoch and Phil Stevenson, have an (unproven) theory that caffeine in the lime nectar may be affecting the bees’ judgement – “Lime trees are noted for their far reaching, sweet scent. Maybe this odour together with caffeine in the flowers could result in a fatal attraction of the bees to the point where they run out of energy and starve?”.

A final update – in 2019 researchers published this paper: Linden (Tilia cordata) associated bumble bee mortality: Metabolomic analysis of nectar and bee muscle, proposing that a “combination of low temperature and nectar volume, resource fidelity, and alkaloids in nectar could explain the unique phenomenon of bumble bee mortality associated with linden”. As of 2020 this is the most recent research into the topic that I am aware of.

Have you had any experiences of toxic or unpleasant honey, or found bees dead by any of these plants? If so I would be interested to hear about it.

References:

- ‘Bitter sweet nectar: why some flowers poison bees‘ by Stephanie Pain (BBKA News, February 2016, p.51-52)

- ‘How do honey bees react to naturally occurring poisons?’ by Jürgen Tautz (BBKA News, December 2016, p.432)

- ‘Do lime trees kill bees?’ by Hauke Koch and Phil Stevenson (Kew Science Blog, 27 September 2017)

- Collins Beekeeper’s Bible (2010)

- Guide to Bees & Honey, Ted Hooper (2010)

- The Honey Bee Around & About, Celia Davis (2007)

- Practical beekeeping, Clive de Bruyn (1997)

I have read before about plants whose nectar when concentrated into honey can be dangerous to humans.

Being the cautious person I am, I don’t buy unprocessed honey (not foolproof, but minimizes risk).

I have a “Book of Poisons” which is mostly a resource for writers, and it includes a section on poisonous plants. Many of the listed poisons include case studies of crimes committed with them.

One section says “The Greeks found that honey from bees that fed on azaleas, rhododendrons, oleander, or dwarf laurel was poisonous.” There were no case studies involving honey, but that just means no police or medical report.

LikeLike

I think not buying unprocessed honey is over-cautious, but of course it’s up to you. The cases of poisoning are extremely rare and in most cases where poisonous plants are present beekeepers are aware and take steps to avoid selling such honey.

Usually unprocessed local honey is actually much higher quality, as heating the honey like commercial producers do affects the taste and nutritional value.

LikeLike

Absolutely fascinating! I’ll never look at (or taste) honey in the same way again! (BTW, good luck with your exam in Nov!)

LikeLike

Thank you – I’ll need the luck for sure!

LikeLike

Very interesting how when you can isolate and produce some of the monofloral honeys such as Manuka,Ulmo Buckwheat and Heather, they have useful medicinal characteristics and yet still others are toxic and hallucinogenic. Maybe we just have not discovered a use for them yet.

In the North Island of New Zealand( and the top of the South Island) they have a poison Honeydew honey which requires careful management..

It comes from a bush, common in stream valleys,called Tutu (Coriana arborea) which contains a poison called Tutin in its sap. Around January this bush is often infested by the Passion Vine Hopper (Scolypopa sp) which feeds on the sap and excretes large amounts of a sugary honeydew which is very attractive to honeybees, but also contains the poison Tutin, .

People have died eating HONEYCOMB containing only this honey and beekeepers have to be aware and comply with government regulation- Food (Tutin in Honey) Standard 2010 -to prevent quantities getting into commercial honey. Extracted and mixed with other honeys in small quantities it is harmless.

Passion Vine Hopper Honey is definitely ‘a bad idea’.

LikeLike

Ah yes I came across the Tutin honeydew poison in my reading. Glad we don’t have that over here, sounds like a pain in the butt.

LikeLike

Fascinating reading Emily. My thoughts also go to the pharmaceutical knowledge that bees have instinctively. They may just know exactly what they are doing taking the nectars and pollen from these plants we call poisonous. For them they may make the difference between a healthy colony or a weak colony. One man’s bread is another man’s poison might work for them too. It might also be their watch dog system so that we don’t pinch all their lovely stuff for ourselves without a thought for them and then give them a substitute in return. Who do we think we are kidding?

LikeLike

I’m not sure about them knowing instinctively, but I do wonder if honeybees have more sense for this, or more sensitive tastebuds, than bumblebees. Usually when piles of bees are found dead under a lime tree they’re bumbles.

Usually when horses get poisoned by ragwort it’s the fault of humans. When horses taste the fresh ragwort plant they taste the bitterness and avoid it. However if humans feed horses hay containing dry ragwort, the ragwort has lost its bitterness and the horses can no longer detect the alkaloids.

LikeLike

Very interesting. I didn’t realize that the Ivy’s flower would also give honey a bad taste. I’ve known about the Rhododendron and watched a documentary highlighting the toxicity on a flight to Asia. It’s on YouTube now- “Hallucinogen Honey Hunters” by Raphael Treza. It’s a very interesting documentary about Nepalese honey hunters.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the tip about the documentary, I’ll watch that for sure.

LikeLike

Glad we only have 1 rhododendron! We have mountain laurel scattered in the woods and in front of the house, but hardly enough to compete with all the other good stuff around here. That documentary sounds interesting!

LikeLike

Hopefully you’ll be ok then. I’m looking forward to watching the documentary. Would love to see wild honey collecting for real one day.

LikeLike

Valium is an example of a benzodiazepine drug but I don’t think lime trees contain actual benzodiazepines. There are some reports of limes containing chemicals that may have the same activity as benzodiazepines i.e. sedative but these are more likely to be flavonoids, although the work is incomplete as far as I can see.

LikeLike

I got that information from one of my books – perhaps it is incorrect then. Hmm, wish I knew for sure.

LikeLike

Emily, I find your blog fascinating. I’m new to beekeeping, presently worrying about wintering my two colonies & reading all I can. Good luck with your exam.

LikeLike

Thanks Gill, really glad you like my blog. Whereabouts do you live? If you’re doing lots of reading I’m sure your colonies will be well looked after.

LikeLike

Apparently Lime trees have active Benzodiazepine receptor ligands which makes preparations from them dangerous to use in conjunction with benzodiazepine drugs.( Viola Wolfmann et al)

I have just returned from Valletta Malta where the Knights of St John built in 1574 a 155 metre long hospital hall with individual toilet facilities and curtained cubicles. Meals for ordinary folk were served on silver utensils for hygiene and FRESH HONEY was used for wound treatment very successfully. The enormous single span ceiling beams were from lime trees.(linden)

LikeLike

Thank you Jonathan. I tried reading the Wikipedia entry for receptor ligands but didn’t really understand it to be honest – would you be able to explain what they are in simple words for a non-scientist like me?!

What an amazing hospital the Knights built, amazing that they had such a sense of hygiene at a time when people didn’t know about germs. They did well using honey too.

LikeLike

Probably not, as I also am a non scientist hobby beekeeper with a particular interest in healing honeys.

However It would seem that the membranes of cells contain receptors and ligands. When a ligand from one cell binds with a receptor of another cell it causes changes in the receptor cell which then causes further reactions.

It could be that drinking a Lime flower infusion sweetened with Lime honey from certain trees while on Valium could have an unexpected further effect.

I was really hoping that PhilipStrange would come back since he raised the matter of flavonoids in the Lime honey.

LikeLike

Thanks Jonathan, Philip has replied now. I like your idea of drinking the lime infusion, honey and valium combo! Quite a cocktail. One for the Ealing beekeepers Christmas party, it might even knock people out more than the home-brewed mead usually does.

LikeLike

I apologise if I have caused any confusion but let me try to explain the situation.

Extracts of Tilia (Lime) species are used traditionally in Latin America for sedation/tranquilising/anti-anxiety. Given the widespread use of benzodiazepine drugs (such as Valium) to treat anxiety there was great interest in looking to see if natural treatments for anxiety contained chemicals similar to benzodiazepines. There are one or two papers examining Tilia extracts and the Viola et al paper (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0378874194900981) quoted by Wikipedia is the most comprehensive. I have only been able to read the abstract as I can’t access the full paper but I will try to explain what they did.

To do this work you need to start with an assay that detects the chemicals. The benzodiazepine drugs themselves bind to a site in the human brain to exert their anti-anxiety effects. This site is called the benzodiazepine receptor (it detects/receives the benzodiazepine) and any chemical that binds to this site is called a benzodiazepine receptor ligand. (Ligand is just a fancy scientific name for one molecule that binds to another). So the assay looks to see if chemicals in Tilia extracts bind to this receptor.

In their paper, Viola et al, did just that; they made extracts of Tilia and looked to see if there were any molecules that bound to the benzodiazepine receptors. They did find one substance called kaempferol but they showed that it didn’t bind very tightly and when they tested it in a mouse behavioural model for anxiety it was inactive. That was really the end of the story but they did also test a crude Tilia extract in a mouse behavioural model for anxiety and showed that the Tilia extract had anti-anxiety effects (in the mouse model). There are other papers showing the same but no active molecules have been isolated and characterised.

So, you could say that Tilia contains “benzodiazepine receptor ligands” but the one that has been characterised is inactive and although the behavioural tests show that there may be other active chemicals in the extract, they have not been characterised.

I am sorry that this is such an unsatisfactory story but science is like that sometimes. It is important that scientists don’t claim too much for their work and I would say that the Wikipedia entry already does that.

I hope this has been understandable but I am happy to answer any questions etc.

LikeLike

Thanks very much Philip, this makes much more sense to me.

LikeLike

In writing the comment above, I did find the following information at the Bumblebee Conservation Trust (http://bumblebeeconservation.org/about-bees/faqs/finding-dead-bees/) which shows that it is not a toxic substance in limes that kills bumblebees but a facet of their behaviour. It seems they continue feeding on lime nectar even when levels are low and so they run out of energy. Honeybees don’t do this, they look elsewhere before they exhaust themselves.

LikeLike

Interesting, thank you. I will update the post to reflect this when I get a chance. It seems there has been some disagreement on the topic, which would explain why some of my books class lime nectar as toxic. I still wonder what it is about lime trees that makes bumbles continue feeding. Perhaps it is just that they’re struggling to find alternative nectar sources at that time of year.

LikeLike

That’s really interesting about rhododendron honey. The Rhododendron is the Washington State Flower, and I’ve been keeping bees here for over a decade, involved in bee clubs and such and had never heard that! They grow everywhere here, but are mostly pollinated by bumble bees and other larger pollinators. We sometimes see honey bees in them, but not much. Perhaps it’s only toxic if it’s the only floral source?

LikeLike

I expect that is the case, especially as it seems honey bees don’t visit the rhododendrons much if they have the choice. You’d probably know if your honey made people delirious by now!

LikeLike

Ooh, just came across this great article on how ‘mad’ rhododendron honey is made in Turkey – http://modernfarmer.com/2014/09/strange-history-hallucinogenic-mad-honey/

LikeLike

Thank you Philip for explaining the research and findings but having reached the end of that story ,it would seem that there is still more to be done to find how the Lime extracts are actually producing the anti anxiety effects in mice.(and men!)

I read somewhere that the waggle dance language of the bees communicates among other things exactly how much honey fuel to load up to get to the good new nectar source and run out, so that a full payload can be brought back,( allowing for headwind or tail wind). Could it be this function of constant redirection in the hive of Honey bees that prevents them exhausting themselves as the Bumbles sometimes appear to do on the Lime. They certainly seem to be cannier.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating! In our area (northern California) we have quite a lot of buckeye, the nectar of which is toxic to bees – in a good year the blackberry is blooming at the same time and the bees go for that instead, but last year we had a late blackberry honey flow and we did find piles of dead bees in front of a few of our hives, likely due to buckeye nectar. You’d think they would know better! Fortunately this was a good blackberry year, so we didn’t have a buckeye problem. Thanks for the great post – now I’m curious to try ivy honey!

LikeLike

Interesting, thanks Julia. I didn’t know buckeye (horse chestnut?) was toxic, I’d always thought of it as a good bee tree. Glad your bees were ok this year.

LikeLike

Congratulations on your illuminating blog,with Ivy honey addicts, lime potions and ‘trips’ to Turkey,it can only be described as ‘mind blowing’!

One other UK source of funny honey is Honeydew which bees gather from several trees when leaves are attacked by aphids,The honey produced is thick dark and treacly and smells of stewed fruit.

The aphids absorb the sap proteins but excrete surplus sugars onto the leaves to be collected enthusiastically by ants and bees,also the aphid wounds to the leaves carry on dripping sap.

Sycamores in early summer sometimes have drunk bees on the ground beneath where the natural yeast on the leaves ferments the honeydew to alcohol. and the same can happen with Lime trees later in the season.

This does not happen every year depending on weather humidity and degree of aphid infestations.

Black honeydew honey from pine trees is highly esteemed on the continent.

LikeLike

Thanks Jonathan! I did think about including honeydew, but the syllabus specifically says floral sources of unpalatable honey, so I think they’re not looking for honeydew as an answer. I’d be curious to try it – have you had any?

LikeLike

Yes Emily I have but its odd taste of burnt jam was not marketable so I mixed it back with other honeys and said how lovely rich and dark the crop was that year!! Like your allotment hive!

Black Wald honey is much prized in medicine abroad but not appreciated here.

Coleridge in his accidentally opium induced Kublai Khan poem refers to the effects of taking honeydew, as in Tutin NewZealand they can contain interesting things medically.

LikeLike

This is great! Do you have any advice for plants for bees in Tanzania?? We are just starting a bee project here! Thanks! http://themongers.blogspot.com/2014/10/the-riverbed-road-and-bee-invitation.html

LikeLike

Thanks Rachel, I have signed up for your blog.

Sorry but I wouldn’t know about plants for Tanzania as our climate is so different. Generally it’s always best to use local plants that all the native pollinators will enjoy. Honey bees are generalists and adapt well to a variety of flowers, they’re not too fussy. Wild flowers are usually the best.

LikeLike

Pingback: Winter studies: The poison honey | Miss Apis Mellifera

This suddenly turned up on my email – but it’s great, so a belated comment:

Brilliant blog, as usual, Emily – I will comment on the Seattle “Rhododendron Poison Honey” case sited. As you can imagine it created a huge stir in the Seattle Farmers Market circles (where I sell honey).

I called the scientist who did the assessment of the honey, and he told me a few facts that were NOT reported.

1) He was asked to ONLY test for the presence of Rhododendron in the honey.

2) He was NOT asked about any other potential hazards the bees could have gotten into.

3) He was NOT asked about any other potential hazards that could have gotten into the honey (I know one beekeeper who keeps poisons in the same room as the extractor – go figure)

4) He told me that he NEVER said the person was “poisoned by the honey” – rather he said that the person who was poisoned ate honey that had as a component Rhododendron honey.

The press saying that “the person was poisoned by Rhododendron honey” is kind of like saying I went to the library, and I got the flu – thus going to the library gave me the flu — might have if there were germs there, but might not have.

If one were to eat honey from hives in the middle of a mass of Rhododendrons it would not be good. But there are few thick stands of them in Washington – and one would not put hives there. I suspect the same is true in the UK (OK, Kew Gardens has a nice stand)….

LikeLike

Strange that it took so long, must have been slowly edging its way down the wires!

I will add your comments to the post. You can never trust the media!

Like you say, I expect there are few places where rhododendrons grow in enough profusion to be a problem. A beekeeper is not mentioned as part of the staff in Daphne du Maurier’s classic novel Rebecca – perhaps they were put off by all the rhododendrons everywhere around the Manderley estate.

LikeLike