My notes from our second talk by Scottish bee farmer Tony Harris at Cornwall Beekeepers Association/West Cornwall Beekeepers Association ‘Bit of a Do’ conference this September. I’ve read books on swarm behaviour and studied it for the BBKA’s module exams, but still Tony taught me quite a few new things!

There is “perhaps no more spectacular event in the bees’ lifetime” said Tony – I have to agree with him. This summer I was sitting on a lawn when the nearby swarm I had been planning to collect in a minute suddenly took off. Bees filled the air, before rapidly zooming over my head, disappearing over hedges into the distance. I was sad to lose them, but it was a beautiful sight.

“What’s the earliest swarm you’ve had?” Tony asked the audience. The winner was: 23rd March (this is Cornwall, remember!). According to research by swarm expert Tom Seeley, most wild colonies swarm once in spring, but 40% of those swarms will swarm again before the end of the summer. Seeley’s studies indicate that the average survival rate of wild swarms may be low, with around 80% of swarms moving into natural cavities failing to survive their first winter.

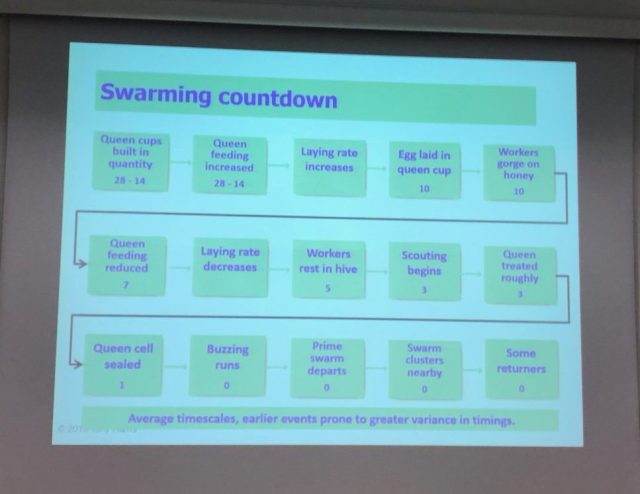

Swarming countdown

Below is a photo I took of one of Tony’s slides, showing the timings leading up to a swarm, which I thought was quite helpful. Bee maths! He showed us some videos of behaviour such as the Dorsoventral abdominal vibration (DVAV) shaking dance, which can be done up to 300 times an hour on the old queen as the first queen cell is sealed. The workers grab hold of the queen and rapidly vibrate her. As a result, her egg laying behaviour is inhibited – she’s being harassed too much to have time to lay! The DVAV dances stop a few hours before the swarm departs. The workers will also do dances on sealed queen cells – communicating with the virgin queen inside.

Composition of a swarm

- 70% of workers less than ten days old leave with the swarm.

- Drones make up less than 1% of the swarm population

Choosing a new home

Once the swarm leaves, they will temporarily settle in a spot (such as an inconveniently high tree – or, for some lucky beekeepers, a low bush!). The swarm sends out a small number of scout bees, who will explore an area of up to 30 square miles in their search for an ideal home. Below is one of Tony’s slides summarising what a perfect bee home looks like, based on research by Winston and Seeley & Morse. Although bees are supposed to prefer high-up locations, Tony noted that he’s had more success with bait hives placed on the ground!

Meanwhile the swarm hangs clustered together. They can maintain their temperature at 35C in their core and 17C for the outside bees, regardless of the ambient temperature that day. The scout bees return to the cluster and carry out waggle dances for the best location they’ve discovered. If it happens to rain, the waggle dances will be paused!

Gradually, a consensus will be reached once all the scout bees are dancing for the same location. When that happens, the cluster will soon take off and head for their new home. If you need to buy yourself some time while you get equipment ready to collect a swarm, Tony suggested gently spraying the hanging swarm with cold water (please don’t train a hose on them!). The reason behind this is that all the bees need to warm their flight muscles up to 35C to be ready to fly.

Virgin queens

Back in the old parent colony, the first virgin to emerge from her cell will often seek out any ‘quacking’ virgins still in their cells. The quacking noise is produced by the virgins vibrating their flight muscles, pressing their thorax against the comb as they do so. The emerged virgin’s sting is long enough to reach her rival queens and kill them before they hatch.

If two virgins emerge at the same time, they may fight, using their mandibles to grasp each other. Another possibility is that a virgin will leave with a secondary ‘cast’ swarm, taking a smaller number of bees off with her.

Aren’t swarms wonderful? As long as they’re not in your chimney, of course. Below are a few photos from my 2019 summer swarms.

Hi Emily

And what was the latest ??- 23rd October here in London last year !!

Clare xx

Sent from my iPad

LikeLike

Wowzers, that would really catch me out! No more swarms please!

LikeLike

Our first swarm this year was 31 March. A friend saw a swarm in the vines in early October this year. It does not beat the London record above and I do not think there is a likelihood of late swarms this year after the dry summer. I agree, it is really something special when you are in the garden with bees swarming around you. You feel they have let you join in. Amelia

LikeLike

It sounds like the French swarming season is similar to southern England then. They do like to keep us busy!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another interesting bee post, we still have a huge amount to learn about their behaviour.

LikeLike

I think so too.

LikeLike

. . . queen bees be ruthless . . . almost human-like.

LikeLike

Yep. But at least they only hurt their own kind.

LikeLike

Funny you should say that . . . I got stung in Halifax while standing at the pier, hundreds of feet away from any flower or visible hive.

It hurt for a few days (and it probably didn’t do the bee much good, either).

However, it was a fluke thing; in raising my camera, I trapped a bee in the crook of my arm (the inside part of the elbow). Not sure why it was there; perhaps it recognized my sweet disposition.

It probably stung in defense to what it saw as being suffocated. Unfortunately, my reaction was to flick it off (it hurt a fair amount) and I immediately regretted it because it probably killed it or at least severely hurt it. Luckily, she didn’t leave the stinger, but she hit right atop the main vein running down my arm.

I don’t want to be a baby about it, but the next few days were not pleasant as far as itching and pain went. Not excruciating pain, but a constant reminder. Luckily, at least this time, I’m not allergic to bee stings.

LikeLike

Youch. Are you positive it was a honey bee and not a wasp though? It’s unusual for a bee to hang out by the sea, whereas wasps are attracted to the sugary things people eat on piers. Either way, most unlucky!

LikeLike

Oh, I had a pretty good look at it. It was not a wasp, it was a small honeybee. Unless there are wasps that look like honeybees.

When I unflexed my powerful arm, it was trying to fly off but the stinger was still attached to my skin, and that’s when I flicked it and probably kill it (I don’t know for sure).

I was on a boardwalk but the shoreline had plenty of flowers. Perhaps it was on its way elsewhere and decided to rest on my arm. Unlucky, that, for both of us. More so her than me.

LikeLike

A swarm is an amazing natural phenomenon. One Friday a few years ago, a swarm appeared above the market square here in Totnes and settled in a tree about 2 metres above the fish stall (no connection). Friday Market is the busiest day of the week and people didnt know how to react, myself included,but it was a privilege to watch. Someone was called to collect the bees but they moved on ahead of the arrival of that person.

LikeLike

That must have caused quite a commotion! A shame that the beekeeper missed them.

LikeLike

Bees are pretty amazing! I love seeing swarms…been keeping bees for years and most of my hives have come from bee swarms

LikeLike

Thanks Jonathan, beautiful aren’t they. I love your company’s name! ‘Stung and sticky’ – brilliant.

LikeLike