A year ago I wrote a post titled ‘How many honey bees are there?‘, after a question on Quora got me intrigued about whether any kind of data exists on worldwide honey bee numbers. Would anyone really have counted?

Well, it turns out they have… sort of.

At the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization website, FAOSTAT, you can now download the latest 2017 data on the number of managed bee hives worldwide across 125 countries (though not my own country, the UK!). The individual country data can be downloaded as a juicy detailed spreadsheet or the data can be visualised in interactive attractive graphs for you in the Visualize data section – this tells us that there was a worldwide total of 90,999,730 hives (up slightly from 90,564,654 hives in 2016).

© FAO, Production of Beehives world total 1961-2017, Web address: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QA/visualize, Accessed: 14/01/19

So the long-term global trend since 1961 is that the number of honey bee colonies has gone up. There have been long-term decreases in the US and some European countries, but these have been made up for by increases elsewhere in the world. More on this later.

That’s the number of hives, but how many bees are there?

So, we want to know the total number of honey bees, not just honey bee hives. Of course the number of honey bees in a hive fluctuates during the year depending on the local weather, season, available forage and the health of the colony. The species or sub-species of honey bee will also affect how many bees are in a colony. Bearing this in mind, I’ve read vastly wide ranging estimates of how many bees are in a colony; but the British Beekeeping Association (BBKA) About bees web section says ‘Typical maximum population is 35,000-50,000’, so let’s go with that.

Allowing for weaker colonies and winter reductions in numbers, as a total guess/very rough and un-mathematical estimate we might say an average of around 20,000 bees could be in each colony.

So we could estimate a total number of honey bees of 90,564,654 x 20,000, which my calculator says = 1.8199946e+12 ! Let’s round that up to two trillion.

However, this number is only for bee hives that have been counted and the data supplied to the United Nations – so it’s likely to refer to colonies being managed by beekeepers. The spreadsheet says the data is ‘Aggregate, may include official, semi-official, estimated or calculated data’. Unless someone out there was clambering up every tree or chimney counting every colony in the land, there will be many more wild colonies that have not been included. And the number of live honey bee colonies will be fluctuating all the time.

Despite the gloomy media reports about declining honey bee numbers, I hope these estimates persuade you that honey bees are not facing the same predicament as the poor Javan rhino (58-68 left). Indeed the long-term trend over the past half-century seems to indicate that the number of hives globally is increasing.

Honey bee numbers are increasing, but crop pollination demand is increasing faster

The problem is not that honey bee numbers are decreasing, but that demand for their crop pollination services has increased. This trend was picked up on by Katherine Harmon in her 2009 Scientific American article Growth Industry: Honeybee Numbers Expand Worldwide as U.S. Decline Continues. She mentions an increase of 45% in domesticated honey bee populations over the 50 years of FAOSTAT data studied by researchers Marcelo A. Aizen and Lawrence D. Harder for their 2009 Current Biology journal paper (The Global Stock of Domesticated Honey Bees Is Growing Slower Than Agricultural Demand for Pollination).

Yet despite this growth in honey bee populations, that’s still dwarfed by the >300% increase in agricultural crops that rely on animal pollination. Aizen and Harder say, ‘The main exceptions to this global increase involve long-term declines in the USA and some European countries, but these are outweighed by rapid growth elsewhere’.

How many honey bees are in the US?

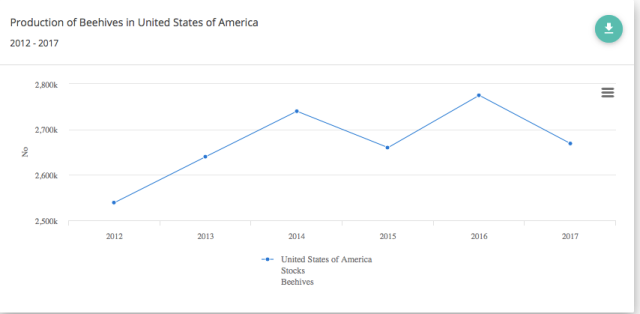

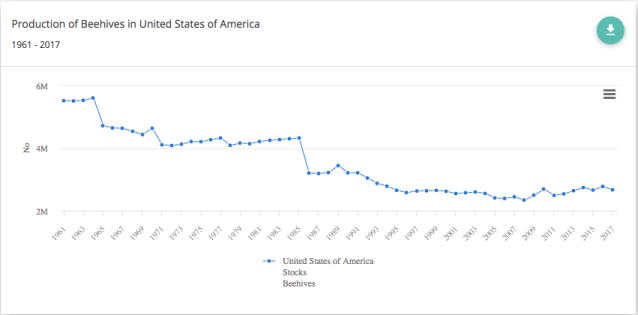

FAOSTAT says there were 2,669,000 hives in the USA in 2017 (the latest year they have available as of June 2019).

If we look at the long-term trend since 1961, the number of beehives in the US has fallen significantly. This bucks the trend in the world totals for beehives having increased since then.

Why are honey bee numbers falling in the US? This is a complex question to answer, but there are some clues in the annual Bee Informed Partnership National Management Survey, which surveys nearly 4,700 US beekeepers. The top ten reasons given for winter colony losses are (in no particular order): don’t know (!), colony collapse disorder, queen failure, weak colony, nosema, varroa, pesticides, small hive beetle, starvation and poor wintering.

How many honey bees are in the UK?

If you’re looking for UK figures… it’s not clear why, but FAOSTAT has no data on numbers of beehives in the UK after 1987; for 1986, it gives the figure 191,000.

Which will make my global estimate even more inaccurate! The UK government does attempt to collect hive numbers through the National Bee Unit – their Hive Count page says:

“2017’s count indicated a total UK population of honey bee hives of approximately 247,000. Please note that several assumptions formed part of the calculations used to get derive this number. It is therefore classed as an ‘experimental statistic’.”

So: an estimate of 247,000 hives in the UK in 2017. That compares to a count of 223,000 in 2016.

In the UK too, it looks like managed honey bee numbers are going up.