Today we visited the Lost Gardens of Heligan and saw the old ‘bee boles’. These are recesses in a wall big enough to hold straw skeps. The wall would have provided shelter and typically would have been south or east facing. At Heligan most of the boles have removable wooden doors in place. I would be interested to know how the wooden doors would have been used. I’m guessing they may have been in place over winter to provide extra protection from the wind and rain and then removed come spring?

Heligan Gardens bee boles

Bee bole and skep at Heligan gardens, Cornwall

The International Bee Research Association (IBRA) maintains a Bee Boles Register which currently contains records for 1589 UK sites, 58 of which are in Cornwall. So I have plenty more to find! And having just checked their Heligan Gardens record, it indeed says the wooden doors were closed in winter and hessian curtains added when very cold.

Skep making is a lovely skill and the skeps are beautiful objects which are still useful for swarm collecting. However I am glad the heyday of skeps has passed, since the bees were often driven out or killed in order for the beekeeper to harvest their honey and wax.

Bee hives were marked on Heligan’s garden map, so I was hoping to see some, but was disappointed to see a sign instead, informing me that the Heligan colony had died out over winter.

There were several information posters about the Black honey bee…

The history of the Black honey bee

Black honey bee better adapted

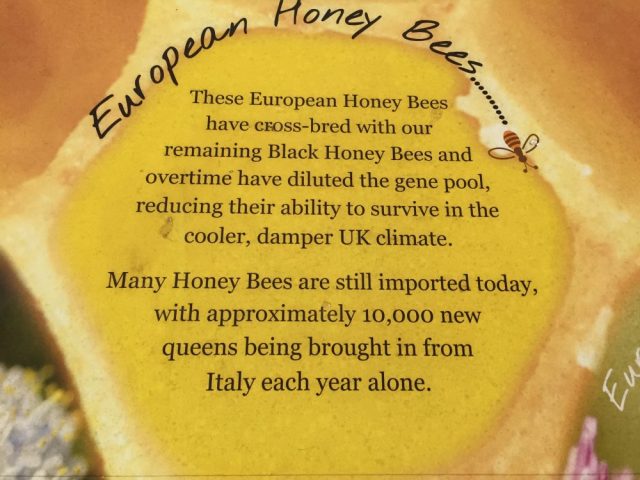

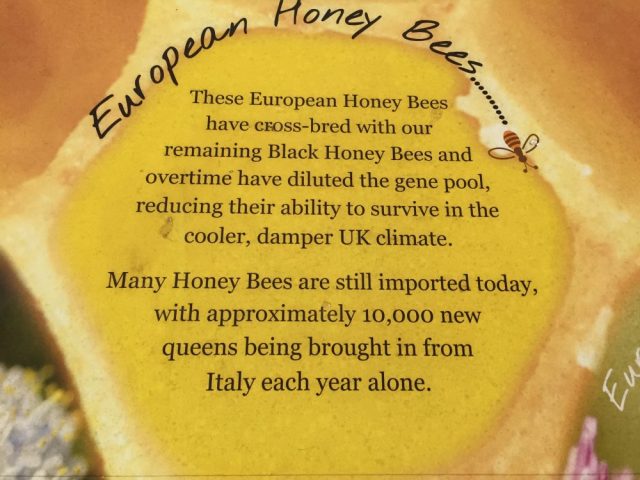

European honey bees

B4 project info

You can find out more about the B4 project at b4project.co.uk. They describe themselves as a “group of beekeepers whose aim is to protect the UK’s native honey bee, Apis mellifera mellifera.” A native dark honeybee reserve has just opened on the Rame Peninsula in Cornwall, as featured in a recent Countryfile episode which I intend to watch soon (8 days left to watch!). From what I read on the BBKA Facebook group, the beekeepers filmed for the episode were not entirely happy with the editing of the show and the final quotes used.

I believe the disease referred to above is a mystery disease that ravaged British bees in the early twentieth century, the cause of which experts have since ventured a guess at. It was first observed in 1906 upon the Isle of Wight. Beekeepers there noticed that their bees were crawling on the ground around their hives, dying so fast that whole colonies were wiped out at the height of summer, when they should have been most strong.

The devastating affliction reoccurred at least three times from 1906 to 1919. By 1907 the disease had wiped out most of the bees on the island – it then spread to mainland England and wreaked havoc there. Huge numbers of bees had to be imported from Europe, so much so that some beekeepers claimed our black honey bee, the darker British subspecies of Apis mellifera, had effectively become extinct.

Looking back at 1906, when the disease first emerged, there was a gorgeously sunny April, drawing crowds to the Isle of Wight beaches. This was followed by an absurdly cold May – frosts and temperatures as low as -5°C (23°F), even in London. It was too cold for honey bees to venture out, at a time when colonies were full of young, spring bees. This created ideal conditions for a number of problems and parasites to take hold – such as dysentery (diarrhoea) due to the bees being unable to take cleansing flights. Of course if bees begin defecating on the combs this can spread nosema, if it happens to be present. Acarine mites can also spread easily from bee to bee due to the number of bees squashed in together tightly.

Although investigations in 1919 revealed the presence of acarine mites in all afflicted hives on the Isle of Wight, leading to the mites being identified as the likely culprit, it’s now thought that the crawling behaviour observed was probably due to Chronic Bee Paralysis Virus (CBPV). It was in the 1950’s that Dr Leslie Bailey (who worked in the Bee Disease Section of the Rothamsted Research Station) first suggested that CBPV was spread by the mite, with many of the colony losses in the 1910s ultimately being due to attack by this virus.

Possibly the combination of unseasonably cold weather, CBPV and acarine mites was a potent one which proved too much for the bees. Diseases and parasites such as nosema, acarine and varroa may not always kill colonies outright, but can weaken the immune systems of the bees, allowing viral infections to take hold. We can’t know for sure what afflicted the bees back then, but the descriptions given by beekeepers at the time of crawling bees with trembling wings do sound like CBPV.

Anyway, I enjoyed my visit to Heligan and hope I can see some of the few surviving black honey bees soon, now that I’m living in the right place. Have any of my readers been lucky enough to spot them, perhaps in Cornwall or at the Black bee reserve on the Scottish islands of Colonsay & Oronsay?